Developing Perspective for FY 2026 Appropriations for Indian Affairs and Indian Health Service

With the Senate passage of an appropriations minibus including the Interior and Environment, Commerce and Energy and Water bills, it’s good to take a moment to both celebrate and reflect. First, congratulations to the House and Senate appropriators who were dealt a difficult hand and still pulled out a bipartisan bill.

Following the passage of a bill like the recent minibus, we look at the topline numbers. IHS is funded at $8.05 billion, an decrease of over $170 million due to low estimates for 105(l) and CSC in FY 2026. (See note at end of this blog post regarding budget scoring that can impact the calculation of the change from FY 2025). Indian Affairs is roughly flat at $4.0 billion, with no reductions overall to the major operating accounts, and a few targeted increases for law enforcement, natural resources and probate case processing. As a result, the initial reaction is often along the lines of, “Phew, the Administration’s significant proposed cuts were entirely rejected, and the bipartisan bill has some targeted increases here and there - looks pretty good given the situation.” But it’s also somewhat like celebrating the passage of a hurricane that largely missed us but left a good bit of flooding and long-term damage in other areas. It's important at times like these to step back and look where we are after muddling through a year of norm changes - especially with the FY 2027 President’s budget and appropriations process about to start in the next month or two.

I’m a fan of benchmarks, especially during times of significant change. I want to set some benchmark information about the budgets for IHS and IA Tribal Programs (think Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Indian Education, Bureau of Trust Funds Administration, Office of Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs). They are impacted by the following trends:

(1) legally required payments for 105(l) Tribal Leases and Contract Support Costs are squeezing other programs, as I anticipated,

(2) costs from other agencies have been shifted to the Indian Affairs budget, and

(3) progress on Indian Water Rights Settlements is slowing.

These negative trends are increased because the last four budgets for Indian Affairs have been relatively flat or declining and have not included fixed costs to address annual inflationary increases. In the post below and two more to follow, I’ll set some benchmark information to inform upcoming decisions by the Administration and Congress. Next, there will be a set of posts on impacts from decreased transparency in the budget process.

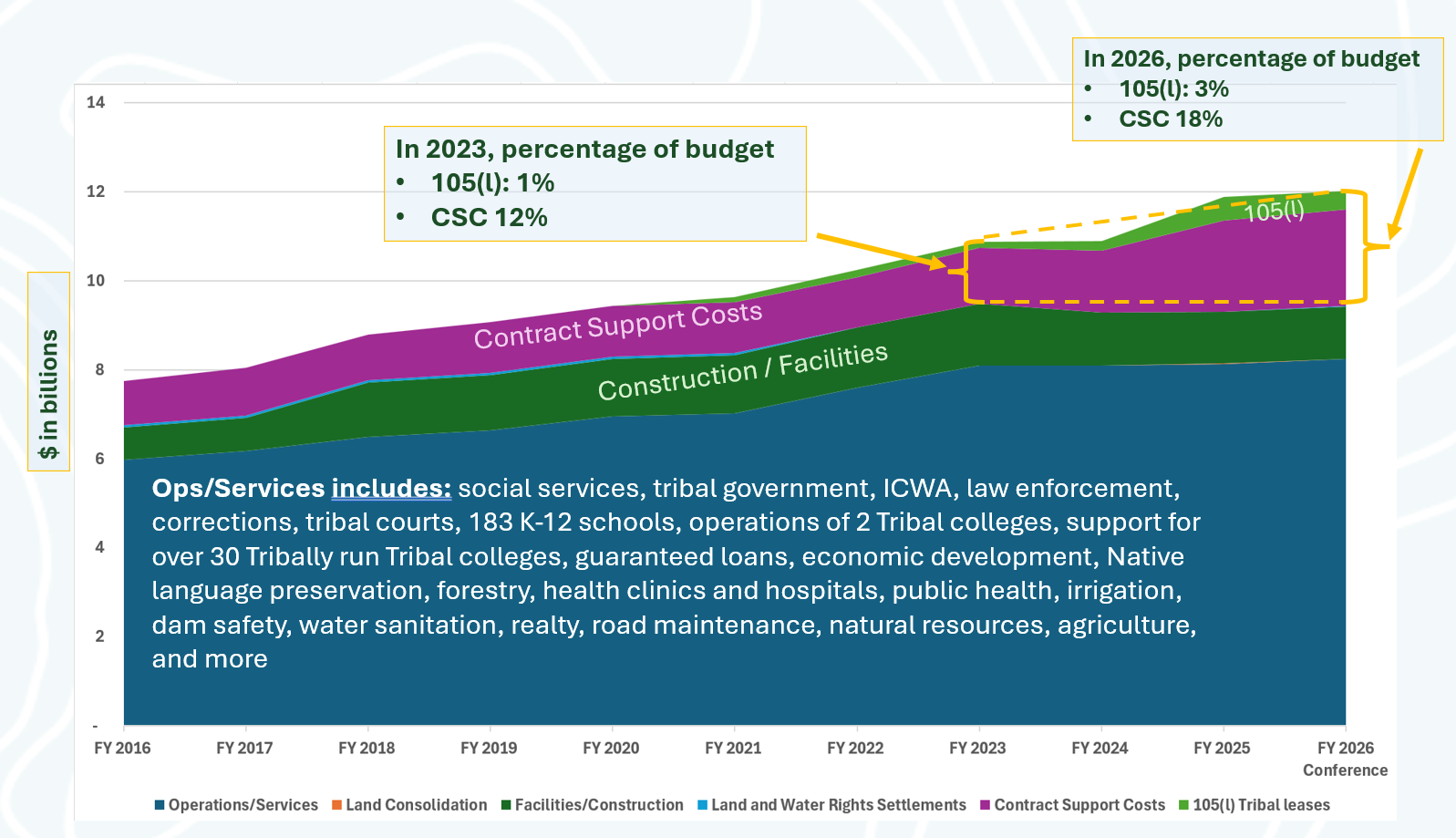

Issue 1: 105(l) Tribal Leases and Contract Support Costs (CSC) are squeezing out funding for other programs. Since FY 2022, funding at IHS and IA for operations and construction has declined as a percentage of their total budgets, while CSC and 105(l) grow as a percentage, as the chart below shows. The IHS and IA budgets totaled $10.9 billion in 2023 and now stand at $12 billion in 2026—a $1.14 billion increase. But here's the catch: the cost of 105(l) and CSC grew by $1.19 billion during those years, meaning other parts of the IA and IHS budgets, primarily facilities and construction, were reduced. During the same period, IA and IHS have not received fixed costs (inflation adjustments). Therefore, the agencies are largely treading water or underwater to address their Trust and Treaty responsibilities.

Long Term Trends for IA and IHS Budgets: 105(l) and CSC taking on Larger Share

The graph shows the long-term budget trend for the combined budgets of Indian Affairs and IHS, highlighting how growing in CSC and 105(l) is squeezing out other costs like construction and facilities management.

What are 105(l) Tribal leases and Contract Support Costs?

First, for folks who are newer to Indian Country here’s some basic info on 105(l) and CSC. Both are legally required payments under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (PL 93-638) and confirmed by Court decisions. Contract Support Costs are the necessary and reasonable costs associated with administering the contracts and compacts through which Tribes assume direct responsibility from IHS, BIA, and BIE. 105(l) Tribal leases are the necessary and reasonable costs the Federal Government must pay to Tribes and Tribal Organizations for facilities costs associated with contracted and compacted activities. While ISDEAA is nearly 50 years old, dedicated 105(l) appropriations only started in 2021. The section 105(l) program has grown significantly from executing three leases in 2019 to Tribes proposing more than 400 renewal or new leases by 2023. Outside of the legal requirement to pay these costs they are critical for advancing self-determination and economic development. CSC ensures Tribes have necessary administrative support to implement contracted programs. 105(l) has become the most innovative tool in a generation for Tribes to increase facility infrastructure investments to properly maintain current facilities and build new facilities for health care, education, public safety, and other services. For more information, review this Congressional Research Service report on Tribal Self-Determination Policies (see pages 12-13).

Why does the growth in these costs matter?

The FY 2026 conference agreement for the entire Interior and Environment appropriations bill totaled $42.5 billion, and was roughly $800 million below FY 2025 levels, about a two percent reduction. If budgets remain flat or decline, the challenge of funding legally required payments will increase. The need to address an increase in legally required payments can lead to overlooking the need to fund basic programs.

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights’ Broken Promises report documents the underfunding of Trust and Treaty Requirements in detail. A good place to focus is IA Public Safety and Justice funding. BIA’s 2021Tribal Law and Order Act report, which calculated the need for law enforcement, estimated that BIA needed over $3 billion more than current funding levels to get to a proper level of funding for an adequate number of investigators and corrections staff and support for Tribal Courts.

On the Facilities and Construction side, high levels of deferred maintenance for BIA dams, irrigation systems, and law enforcement facilities, as well as BIE schools, are well documented. Funding for these programs has declined overall since FY 2022, while construction costs and facility needs have increased while older buildings remain in use. As a reference point, construction costs for nonresidential buildings rose 12.8% in 2022, followed by 5.6% in 2023 and 3.2% in 2024, a cumulative increase of approximately 22% since 2022 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Further, the authorization for the Great American Outdoors Act Legacy Restoration Fund expired at the end of September 2025. As a result, Indian Affairs is no longer receiving $95 million a year for BIE school construction which has been critical for helping BIE keep up with increased construction costs. There does appear to be bipartisan support to reauthorize the Legacy Restoration Fund, maybe this summer, but funding will still be delayed for at least a year - if it is reauthorized.

The Tribal Leader Budget developed within the Tribal Interior Budget Council made an initial estimate of Indian Affairs budget needs of over $27 billion for FY 2026, as compared to $4 billion appropriated in FY 2026. This was not a full estimate of need, but it gives you a sense of the difference in scale between current funding levels and need. For IHS, there is a similar need for funding, albeit even greater. The National Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup for the IHS budget has regularly estimated IHS needs at over $60 billion, compared with the $8 billion appropriated in FY 2026. These budget estimates don’t factor in another new cost to IA and IHS, legislation was recently enacted providing Federal recognition for the Lumbee Tribe. This is the ongoing tension, the Federal government continues to expand obligations to Tribes, but is having a hard time funding those obligations.

The pressure is not just on Indian Country programs. It's also important to note that the squeeze on 105(l) and CSC funding has ancillary effects on other programs in the Interior and Environment appropriations bill. The Interior-Environment Appropriations also funds other Interior bureaus like the National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Smithsonian Institution. Further, these budgets are affected by the rising costs of legally required payments.

So, what can be done? The ideal solution is to reclassify CSC and 105(l) as mandatory funding, so they no longer compete with discretionary investments. This was proposed by prior Administrations and included in previous Senate appropriations bill markups. So, while there has been momentum, it is a big lift in the current fiscal climate. Pressure may build, as it did with wildland fire suppression costs, to finally get to mandatory funding or a creative solution like the Wildland Fire Suppression Cap Adjustment, but there is no guarantee. A more incremental, but not easy, solution would be for Congress to ensure adequate discretionary funding increases for IA and IHS operational and facility programs.

Note about 105(l) and CSC budget scoring: The FY 2026 President’s budget and FY 2026 Appropriations statement of managers have inconsistent approaches to the FY 2025 budget score for CSC and 105(l). Since they are used more widely, and to reduce confusion, I updated my numbers to reflect the CBO estimates in the FY 2026 Appropriations statement of managers table of requirements. The drawback of updating the numbers is that I think the CBO estimates for FY 2026 are on the low end, and using CBO’s high 2025 estimates makes it look like there is a larger decrease than there really is.